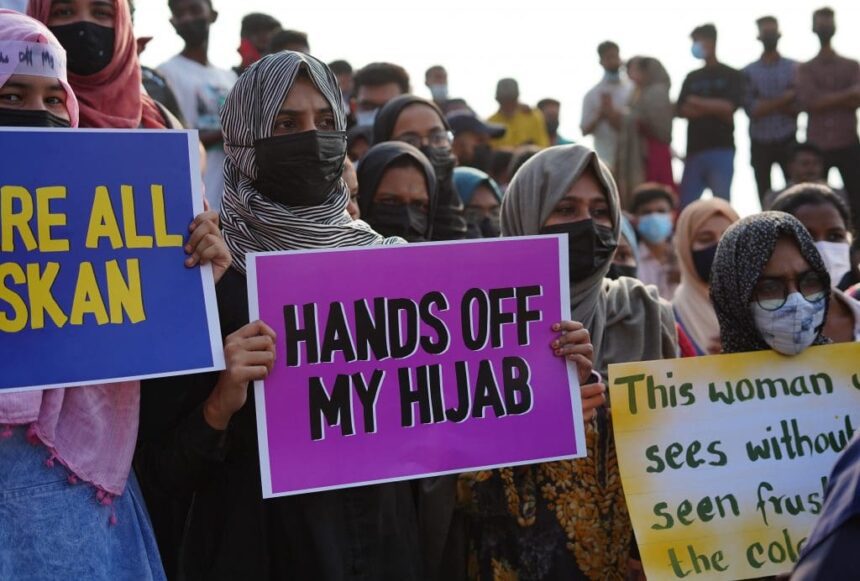

The hijab has long been a contentious symbol within secular public discourse, often portrayed as a marker of backwardness, coercion, or a troubling religiosity. When the veiling of Muslim women is scrutinized, banned, or interfered with, it often reveals the most insidious forms of Islamophobia, particularly gendered Islamophobia. Scholars such as Jasmine Zine, Alimahomed-Wilson, and Lila Abu-Lughod have theorized this concept, with Zine characterizing it as “a form of racialized gender violence that targets Muslim women through intersecting regimes of patriarchy, racism, and imperialism.”

The public unveiling of a Muslim woman at an official event by Bihar Chief Minister Nitish Kumar exemplifies a political culture that embodies gendered Islamophobia, where Muslim women are both hyper-visible and simultaneously stripped of agency. In this context, veiling becomes a symbolic battleground for anxieties regarding secularism, national identity, and modernity.

Feminist scholarship on the hijab has evolved from a binary understanding toward a more nuanced consideration of its cultural and political implications. Western liberal feminists traditionally framed veiling as a sign of patriarchal oppression, equating visibility with emancipation. In her seminal essay “A Vindication of the Rights of Woman,” Mary Wollstonecraft described Muslim women as ‘soulless’ to advocate for the education of Western women, strategically contrasting the civil and barbaric.

Postcolonial feminist scholars, including Mohanty and Mernissi, have challenged the simplistic framework that positions Muslim women as the ‘other’ to Western women. Saba Mahmood’s “Politics of Piety” is pivotal for redefining agency, suggesting that it should encompass ethical self-fashioning within religious traditions, not merely resistance to norms. Moreover, Leila Ahmed’s historical analysis in “A Quiet Revolution” illustrates how veiling has been a complex phenomenon, intertwined with colonial dynamics that portrayed unveiling as civilizational progress while masking imperialist agendas. Such a colonial logic persists in contemporary secular governance, where the hijab remains a focal point for state intervention.

Joan Wallach Scott critiques the fixation on the veil as a strategic displacement for liberal democracies to express their commitment to gender equality while ignoring their own controlling practices. Islamic feminist scholars argue that the debates surrounding the hijab primarily concern controlling Muslim visibility and asserting state authority over minority bodies, rather than genuinely advocating for women’s rights.

The meaning of the hijab has never been singular; its interpretations are contingent and shaped through power-laden interactions. For instance, when the Shah of Iran banned public veiling in 1937, many women chose to remain at home rather than unveil, and hijab later became a symbol of the 1979 Islamic Revolution. When authorities assert the right to question, touch, or remove a woman’s veil, they exercise interpretive sovereignty over her body, reinforcing patterns of domination that feminist critiques aim to dismantle. Unveiling a woman without her consent—whether through physical or symbolic means—asserts power over her body and aligns with broader narratives of violation.

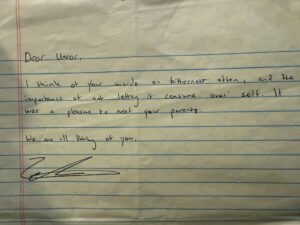

Judith Butler emphasizes that bodies marked by religious and gendered differences are precarious in contexts dominated by state authority. The public sphere is not neutral; instead, it is structured by norms that dictate whose bodies are considered legible and respectable. For Muslim women, veiling heightens this precarity, exposing them to surveillance under the guise of promoting visibility. Their access to public life is often contingent on modifying their appearance, suggesting that their acceptance is conditional and supervised. Reports, such as that of a Muslim woman doctor in Bihar who felt humiliated after being forcibly unveiled, exemplify this reality.

Understanding gendered Islamophobia reveals its intimate nature, operating through societal concern and moral anxiety. It primarily targets visible Muslim women in hijab and burkas, framing them as both victims in need of rescue and symbols of cultural excess that must be controlled. Consequently, these women face heightened scrutiny of their dress, mobility, and behavior, monitored not just by state institutions but also by the media and public opinion. This surveillance often manifests through everyday interactions and language that normalize domination while appearing benign.

The notion that Muslim women must unveil to be recognized echoes historical imperial interventions that imposed emancipation rather than honoring choice. There is a colonial continuum that equates visibility with progress and conformity with acceptance. The persistent scrutiny of hijab in public life necessitates a rethinking of feminist politics today. Any feminist framework attentive to power, difference, and history must reject the regulation of Muslim women’s bodies as a pathway to equality. Consent and bodily autonomy must apply equally across the board. It is evident that the hijab itself is not the primary site of oppression; rather, it is the ongoing surveillance and control of Muslim women’s bodies that should be critically examined.

Tags: When hijab becomes a public problem: understanding gendered Islamophobia Extract 5 SEO-friendly keywords as tags. Output only keywords, comma separated.

Hashtags: #hijab #public #problem #understanding #gendered #Islamophobia