Hana Muneer & Abdullah Alwi

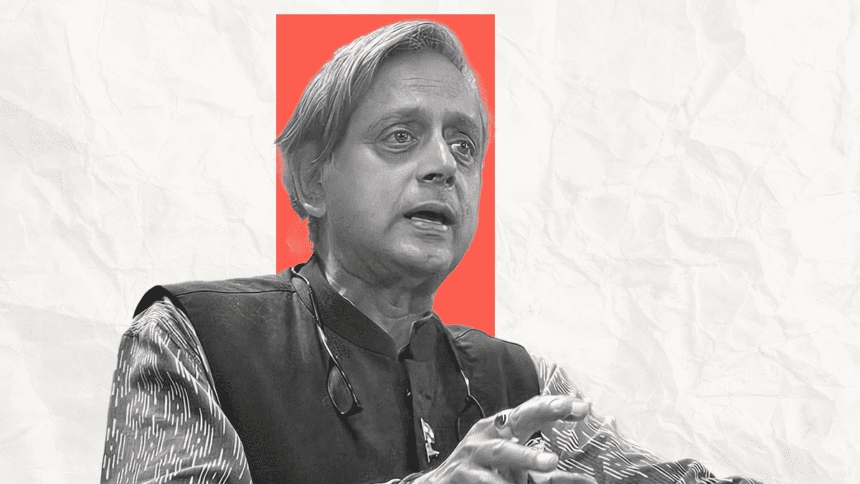

Member of Parliament Shashi Tharoor participated as a panellist in a discussion titled “The Future of the Nation-State and National Identity” at the Doha Debates Town Hall during the Bradford Literature Festival 2025. Alongside scholars Dr. Wael Hallaq and Dr. David Engles, Tharoor engaged with a diverse group of students from Qatar and the UK, leading to an in-depth examination of themes such as belonging, sovereignty, and identity. However, the discourse highlighted a significant tension in Tharoor’s assumed civic nationalism, a framework that appears inclusive yet proves fragile when faced with challenges.

Throughout the 90-minute debate, Tharoor demonstrated uncertainty and contradictions in his arguments, especially when confronted with interjections from the audience and fellow panellists. Initially presenting civic nationalism as a framework that transcends ethnic, linguistic, and religious divides, his stance faltered under scrutiny. When the moderator inquired about consequences for dissenters, Tharoor’s response was stark: “They always have the right to opt out, right? Go immigrate to another place if you really don’t believe in this project.”

As a student participant, Hana Muneer raised a pertinent issue related to contemporary India’s socio-political landscape: the alienation faced by minorities whose moral and religious autonomy has been compromised by the state. Her assertion was clear: she felt no sense of belonging, reflecting the real experiences of communities marginalized by systemic exclusions and communal animosity. Tharoor’s response, while courteous, was telling—he offered an apology coupled with assurances about India’s civic nationalism accommodating diversity, citing instances such as female Muslim officers participating in government briefings during Operation Sindoor. Yet such symbolic examples fail to address the deeper systemic inequalities that render citizenship conditional for many.

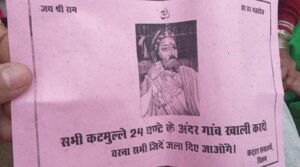

In his opening remarks, Tharoor characterized Operation Sindoor as a conflict of “India versus terrorism,” rather than “India vs. Pakistan” or “Hindu vs. Muslim.” This framing reinforces a problematic war-on-terror narrative that leaves the definition of terrorism vague, granting the state broad authority to delineate who is a “terrorist.” When conflict shifts from an external enemy to an abstract moral dichotomy, dissent risks being perceived as suspicious, as seen in the incarceration of activists like Sharjeel Imam under the UAPA without trial. This subtle shift implies a dangerous expectation that Indian citizens must align with the state’s interpretation of threats, or face exclusion from the national consensus. In this construct, belonging is conditional, reliant on compliance with a security discourse imposed by the state.

In response to Dr. Hallaq’s caution regarding violent outcomes from rigid national belonging during crises, Tharoor differentiated between nationalists and patriots. He defined the nationalist as someone “willing to kill for the nation,” while the patriot is “willing to die for it.” By presenting patriotism as a morally acceptable alternative to nationalism, Tharoor fails to escape nationalism’s inherent violence; he merely presents it in a more palatable form. The soldier who sacrifices “for the nation” operates within the same ideological framework that justifies state-sanctioned killings. This distinction obscures the continuum that exists between both concepts.

Tharoor’s assertion that all identities are “kept safe” within the Indian nation-state contradicts perspectives he has previously articulated. In a 2018 opinion piece about the Sabarimala verdict, Tharoor asserted that constitutional principles cannot exist apart from societal acceptance, especially concerning faith matters. He argued that when constitutional guarantees collide with deeply held religious beliefs, there is a democratic obligation to prioritize the sentiments of the religious majority. This flexibility is notably absent when discussing the alienation of minorities. While the discomfort of Hindu worshippers at Sabarimala is viewed as a legitimate concern, the unease of religious minorities in the nation-state is met with appeals to constitutional loyalty and, ultimately, the suggestion to “opt out.”

Another vital yet overlooked aspect of the discussion is the shift from rights-based language to a focus on enablement. Tharoor started by stating, “to demand what I am entitled to,” explaining how Muslims should utilize their constitutional rights to improve the nation. However, he quickly transitioned to the notion that citizenship “depends on what the political organization enables you to do.” This implies a vision of states as enablers, positioning the state as a source of empowerment rather than a guarantor of rights.

When Tharoor claims that a state should “enable you to flourish,” the dynamic significantly alters. This semantic shift is not insignificant; it suggests that while entitlement denotes a claim against power, enablement implies a privilege granted by it. A state focused merely on enabling can rescind that enablement without infringing upon rights. This concept of “civic nationalism” could swiftly deteriorate into something more insidious as more conditions are introduced. Tharoor’s insistence that the state should “empower you” while simultaneously stating that it must “safeguard a certain amount of space for itself” reveals an unresolved tension.

These discussions at the Bradford Literature Festival 2025 reflect the growing incoherence in Tharoor’s recent political stance, which outwardly appears distinct but is internally fraught with contradictions. Once viewed as a moral counterbalance to the ruling administration, Tharoor’s remarks, particularly the closing statement about opting out, highlight how easily civic nationalism devolves into a form of accommodation where belonging is defended rhetorically yet constrained in practice.

The discomfort generated by this debate suggests a broader issue beyond a single politician. The discourse surrounding civic nationalism and the ideals of “unity in diversity,” often seen as foundational truths, begins to fracture when subjected to scrutiny beyond pre-scripted forums and emotional appeals. For civic nationalism to mean more than mere rhetorical gestures, it must confront these contradictions transparently; otherwise, the distinction between soft-liberal nationalism and the harsher realities of majoritarian politics may be less substantial than it seems, differentiated primarily by tone rather than principle.

Hana Muneer is a media student at Qatar University, and Abdullah Alwi is a Master’s student in Philosophy.

Tags: Shashi Tharoor’s “Opt Out” retort exposes limits of his civic nationalism Extract 5 SEO-friendly keywords as tags. Output only keywords, comma separated.

Hashtags: #Shashi #Tharoors #Opt #retort #exposes #limits #civic #nationalism