Here’s a rephrased version of the content:

On the evening of May 3, 2023, I was in a reading room when a curfew was imposed across various districts in Manipur. An unsettling calm enveloped the area as cars sped by to avoid the restrictions. I had already seen disturbing images of arson on social media, hinting at communal tensions. Initially, I thought it might be a fleeting issue, resolved within days, yet I couldn’t shake off the feeling that this situation could drag on for years. That day marked the beginning of a violent crisis in Manipur.

Now, over two years later, thousands have been displaced, including children, the elderly, and individuals with disabilities. Many infants have only known life in temporary relief camps that have yet to see transformation. What used to be vibrant schools and colleges are now makeshift housing, where families squeeze into single rooms divided only by cloth. At Phayeng High School in Imphal West, classrooms are now shared spaces for lessons and shelter.

After two years of neglect, the prime minister is finally visiting Manipur. Media coverage will return briefly, sparking discussions on politics, accountability, and statistics. While these are crucial topics, what about the children caught in this turmoil?

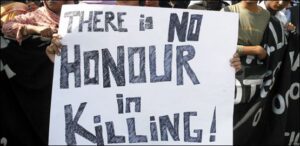

This crisis is not merely humanitarian; it is intergenerational. When we think of Manipur from afar, we often picture its natural beauty, rich culture, or the failures of political leadership. However, we rarely consider the children and adolescents growing up amid chaos, their education disrupted and their youth stolen.

While immediate needs like food and shelter are pressing, we must also prioritize the development of life skills such as empathy, stress management, and decision-making. In conflict zones, UNICEF highlights that these skills become essential for survival. Programs in the Democratic Republic of Congo, for instance, have shown that teaching coping and community skills can significantly reduce PTSD and improve relationships among peers. Adolescence is a critical period for building resilience; toxic stress during this time can have lasting repercussions on brain development and self-esteem.

In Manipur, schools that have reopened tend to focus on academics, neglecting the crucial psychosocial support that is desperately needed. Reports indicate that even financial concessions for displaced children have been revoked, while teachers protest their unpaid salaries. How can we prioritize exams when the need for healing is so urgent?

What do children risk losing? Beyond basic necessities, they require the tools to build livelihoods, manage families, and engage in society. Without these skills, youth often resort to detrimental alternatives such as substance abuse or crime, exacerbated by existing inequalities.

As adolescents in the Northeast and across India prepare to embrace the opportunities presented by the country’s growing economy, those in Manipur face a grim reality. Children in relief camps are left to grapple with feelings of guilt, confusion over their circumstances, and the trauma of losing their homes. While typical teenagers navigate the challenges of puberty and identity, those in Manipur confront displacement, stigma, and societal hatred.

What does this bode for the future? In the absence of safe spaces to process their trauma, frustration can fester. The region already struggles with high unemployment, even among educated individuals. Without essential life skills, the risk is that despair will translate into substance abuse, crime, or deeper societal divisions.

On a national scale, the outlook is even grimmer. For decades, the Northeast has been marginalized and othered, viewed through a lens that reduces it to mere visuals rather than voices. The country pauses for elections and sporting events, but will it ever stop to consider the plight of children in Manipur?

I refused to look away. Leaving my academic career behind, I established the Tengbang Sintha Foundation and launched the Nawa Lousing Life Skills Program. We train young volunteers to support adolescents, teaching them essential skills not as mere theories, but as critical tools for survival. We are also piloting a companion program that ensures children are never left alone with their trauma, and that parents are not burdened with recovery on their own.

Our resources may be limited, and media attention fleeting. However, as Manipur re-emerges in the headlines, I urge us as a society to pause for its children. Can we envision an adolescence for them that extends beyond mere survival?

— Khaidem Nongpoknganba, social entrepreneur and founder of the Tengbang Sintha Foundation, an NGO dedicated to assisting conflict-affected children in Manipur.

This version retains the main ideas while ensuring original wording and flow.