Across India today, and especially in moments of political tension, one question quietly troubles many Muslims who enter public life, contest elections, or work inside political parties: Can I remain true to my Islamic faith while surviving and acting honestly within modern party politics? This question is no longer abstract or philosophical. It comes from lived fear, daily compromise, and repeated moments where silence is demanded in exchange for safety. In an atmosphere where religious identity is constantly politicised, where loyalty is tested through conformity, and where dissent is often punished, the struggle to protect faith while doing politics has become a deeply personal and collective crisis.

This is why the question must be addressed now. Not because Muslims are suddenly entering politics, but because the political environment has changed in ways that place extraordinary pressure on conscience. Today, Muslims in political parties are often expected to choose between being visible and being obedient, between speaking for their community and proving loyalty to the party line, between moral clarity and political survival. The cost of speaking has increased, while the rewards of silence are quietly normalised. In such a moment, faith is not threatened only by open hostility, but by gradual erosion—by rationalised compromise, by selective outrage, and by the slow internalisation of fear.

Abul Ala Maududi, writing in a very different time, warned against precisely this danger when he argued that Islam’s engagement with power must always be ethical before it is strategic. His insight is not about establishing religious rule, but about preserving moral autonomy. Maududi insisted that Islam cannot be reduced to symbolism or identity politics; it must act as a moral force that judges power, not a tool that power uses for legitimacy. This insight is painfully relevant today, when Muslim leaders are often reduced to electoral intermediaries rather than moral actors.

The present political climate makes this struggle sharper because parties increasingly demand total alignment. Politics today is not only about policy disagreements; it is about narrative control. Muslim leaders are asked, implicitly or explicitly, to remain quiet on lynchings, discrimination, or erosion of civil liberties, because raising such issues is framed as “communal,” “inconvenient,” or “electorally risky.” The pressure is subtle but relentless: speak less, adjust tone, wait for the right time, do not upset the balance. Over time, this produces a politics of moral exhaustion.

Fazlur Rahman’s work helps us understand why this is dangerous. He argued that Islamic ethics are meant to guide changing societies through thoughtful engagement, not rigid slogans or empty loyalty. For Rahman, faith survives not through withdrawal from modern institutions, but through critical participation that insists on justice, reason, and social welfare. Applied practically, this means Muslim politicians must treat faith as a guide for decision-making, not as a shield for opportunism. It also means translating moral concern into policy action, not merely symbolic presence.

In real terms, this requires shifting focus from defensive identity politics to constructive institutional engagement. When education outcomes for Muslims remain poor, the response cannot only be speeches about marginalisation; it must include pushing for coaching programmes, monitoring scholarship delivery, improving school infrastructure in neglected areas, and demanding accountability from administrations. When employment is scarce, leaders must negotiate for skill development schemes, fair hiring practices, and local economic investment. Faith is preserved not when leaders display religious identity, but when they protect dignity in everyday life.

Yet, this is precisely where the tension intensifies. Parties often welcome Muslim leaders as vote mobilisers, not as policy negotiators. The expectation is loyalty without leverage. This is why protecting faith within parties requires clarity about non-negotiables. Khaled Abou El-Fadl’s emphasis on moral reasoning is crucial here. He reminds us that justice, mercy, and human dignity are not optional virtues; they are the core of Islamic ethics. A Muslim leader cannot defend policies that harm vulnerable people simply because the party demands unity. Silence in the face of injustice is not neutrality; it is participation.

Another urgent aspect of the present political moment is the shrinking space for dissent. Even lawful disagreement is increasingly framed as betrayal. In such an environment, the temptation to retreat into quiet survival is strong. But Ibn Khaldun’s understanding of social cohesion offers a warning: societies decay when moral leadership collapses under fear. He argued that political power survives only when it is anchored in shared norms and trust. When leaders abandon principle for position, communities lose both representation and hope.

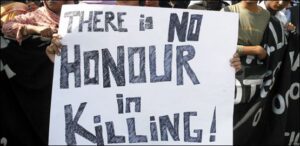

This is why Muslim leaders across different parties must develop what can be called a “moral minimum.” Regardless of party affiliation, there must be a collective agreement on certain red lines: opposition to violence, defence of constitutional rights, protection of religious freedom, and refusal to legitimise hate. This is not party politics; it is civic responsibility. Faith is protected not by isolation, but by shared ethical standards that cross party boundaries.

The present political scenario also exposes another danger: symbolic politics replacing real protection. Wearing religious identity while remaining silent on real suffering weakens faith rather than strengthening it. When leaders are celebrated for proximity to power but fail to secure justice for their people, faith becomes decorative. Real leadership, by contrast, is often slow, unglamorous, and risky. It involves filing questions, demanding data, negotiating budgets, building legal aid networks, and educating communities about their rights.

Perhaps the most difficult challenge today is resisting the idea that survival requires surrender. Many young Muslims watching politics today feel disillusioned because they see leaders compromise too easily. Protecting faith, therefore, also means investing in future leadership. Mentoring young people in law, public administration, media, and grassroots organising is not charity; it is a long-term political strategy. A community survives not through one powerful leader, but through institutions and educated citizens.

Ultimately, the question of protecting Islamic faith within political parties is not about purity or withdrawal. It is about moral courage in imperfect systems. Faith was never meant to guarantee comfort; it was meant to guide conscience. Politics will always involve negotiation, but faith draws the boundary where negotiation must stop.

And so, the question that remains is not whether Muslims can survive in politics, but how they choose to do so. Will faith be reduced to silence for the sake of access, or will it become a living ethic that shapes policy, protects dignity, and challenges power when needed? In this moment of shrinking space and rising fear, what kind of political future are Muslim leaders truly preparing for, and who will pay the price if this question remains unanswered?

Ismail Salahuddin is a researcher and columnist based in Delhi and Kolkata. His work explores Muslim identity, communal politics, caste, and the politics of knowledge. He studied Social Exclusion and Inclusive Policy at Jamia Millia Islamia. His writings have appeared in The Caravan, Al-Jazeera, Frontline, The Wire, Middle East Monitor, Scroll, Outlook India, Muslim Mirror and others.

The post Between conscience and power: Muslim political dilemma today appeared first on Maktoob media.