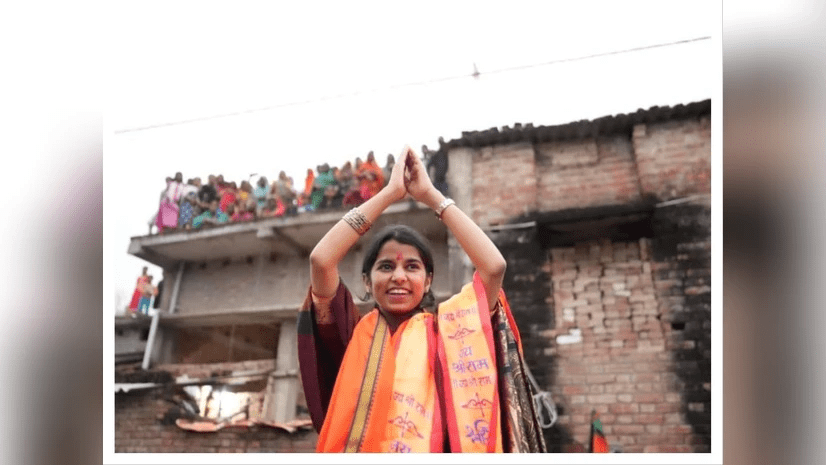

Maithili Thakur’s recent election victory in Bihar has been widely celebrated as a narrative of triumph: that of a young folk singer transitioning into politics. In a landscape often overshadowed by dynasty, corruption, and ideological fatigue, her rise appears to be a refreshing change. However, this ascent is framed by longstanding societal structures that underscore her acceptance. Thakur did not emerge as an outsider; she claims her identity as a Thakur woman, part of a historically dominant upper caste in Bihar that has traditionally enjoyed advantages in terms of land, respect, and political capital. This caste affiliation shapes public perceptions of her, determining which aspects of her past are emphasized and which are overlooked.

Throughout her career, Thakur has navigated diverse musical traditions, including Sufi repertoires, Hindustani styles influenced by Indo-Islamic culture, and Urdu poetry. These genres are often criticized by certain political factions, notably the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which tends to label them as remnants of Mughal excesses or markers of an era that suppressed Hindu civilization. Yet, in Thakur’s case, these associations seem to pose no threat. The same political environment that views Muslim performers with suspicion and Dalit singers as distorters of Hindu culture readily embraces her. Her electoral success indicates not only a generational shift in leadership but also highlights how caste remains central to the discourse of Hindu nationalism regarding inclusion.

Caste and Selective Moral Memory

The ideological acceptance of Thakur within a Hindutva-oriented political sphere is not merely coincidental. It is rooted in an enduring heritage of Brahmanical thought that delineates criteria for what constitutes a respectable Hindu. In this context, purity is perceived as an inherent characteristic of upper-caste individuals. Their behaviors or contradictions do not diminish their claimed purity, as it is considered an innate quality. For example, recent rumors suggesting she had cooked meat—later disproved and revealed as a misinterpretation involving jackfruit curry—did not adversely affect her reputation. Her status within the upper caste affords her a level of protection from stigma, even when engaging with practices labeled as polluting. Activities that might otherwise be politically damaging are perceived as artistic exploration rather than ideological deviations.

Conversely, Dalits and Muslims are often automatically viewed with suspicion, their identities marked as questionable before any actions are scrutinized. This differential treatment explains why Dalit women face moral scrutiny regardless of adherence to strict rituals, while Muslim artists are perceived as external influences even when engaged in deeply rooted Indian cultural expressions.

A similar pattern emerges regarding upper-caste women in various political and cultural domains. Their actions are often interpreted through a lens of prescriptive legitimacy, reinforced by caste dynamics that position them as natural guardians of Hindu respectability. This situation mirrors how upper-caste women shape perceptions of acceptability in public discourse, while Dalit and Bahujan women are often held to stricter standards.

Thus, the aspects of Thakur’s artistic identity that might conflict with BJP’s ideological framework are recontextualized as admirable. Caste not only protects her but also transforms her past into an asset.

Cultural Flexibility and Upper Caste Privilege

Caste privilege is characterized by the ability to traverse cultural boundaries without facing repercussions. Upper-caste Hindus enjoy this leeway in ways that marginalized communities do not. They can exemplify what could be termed ‘performative purity,’ where the claim to purity is dissociated from conduct and instead rooted in caste affiliation. This permits them to consume meat throughout the year while abstaining selectively during festivals, interpreting this intermittent restraint as spiritual discipline rather than contradiction. They may continue wearing the janeu (sacred thread) while consuming meat or alcohol, their caste identities remaining intact—which would not be the case for individuals from scheduled castes.

Moreover, they can partake in or appreciate Urdu poetry and Sufi music without being deemed disloyal. Such engagement with works emerging from Islamic or syncretic traditions is routinely accepted when it comes from upper castes. This social flexibility is unavailable to Dalits and Muslims, whose actions are often viewed through a lens of assumed impurity. For instance, Muslim performers are regularly seen as cultural threats when they engage with traditional Urdu genres or radical works.

The caste system functions to categorize one group as perpetually pure and another as irredeemably impure. Thakur’s ability to navigate diverse cultural realms without jeopardizing her status is indicative of this structure. Her past connections to Sufi traditions do not threaten her acceptance but instead enhance her appeal. Rumors regarding her meat consumption were quickly dismissed, evidencing how caste facilitates her movement across cultural landscapes while preserving her image as a legitimate Hindu figure.

The Ideal Hindu Daughter

In addition to caste dynamics, Thakur’s gendered public persona plays a crucial role in her integration into the BJP narrative. She is often framed as the ideal Hindu daughter, exemplifying traits such as modesty, devotion, and relatability to modern Indian youth. This combination reflects the type of femininity the BJP seeks in women to embody its ideology. Thakur represents a culturally disciplined, non-threatening figure whose moral character remains unquestioned due to the party’s framing of her as an embodiment of Hindu values.

This aligns with analyses of inverted feminist politics, where narratives of female empowerment coalesce with the reinforcement of caste and communal hierarchies. Upper-caste women gain visibility and agency, provided their actions align with existing cultural mandates, while marginalized women remain excluded from this narrative. By symbolizing a respectful, culturally disciplined Hindu woman, Thakur epitomizes this dynamic, enhancing the party’s visibility while minimizing potential political discomfort.

Implications for Hindutva and Caste Relations

From this vantage, Thakur’s electoral win is not a departure from the norm but rather a reiteration of established societal patterns. It underscores the ongoing influence of caste in determining which transgressions are excused, which past behaviors are forgiven, and which cultural adaptability is celebrated. Thakur’s acceptance illustrates that Hindutva’s concern extends beyond safeguarding Hindu identity; it is about upholding the caste hierarchy that delineates who is considered Hindu in the first place. Her culturally syncretic background is absorbed by virtue of her caste identification, making it non-threatening.

This acceptance illustrates Hindutva’s adaptability toward cultural diversity when it is mediated through upper-caste representatives. Conversely, such diversity is intolerable when it emerges from historically marginalized groups. Thakur’s victory serves to highlight the dynamics of caste power in contemporary Indian politics, revealing how discourses around culture, tradition, and nationalism remain shaped by hierarchies that define legitimacy and representation. Ultimately, her story reflects the enduring significance of purity as a measure of societal worth, mediated heavily by caste and religious identity in India.

Vaishnavi Manju Pal, a Gender Studies graduate from SOAS, University of London, serves as a lecturer and module leader of Social Science in London.

Tags: Maithili Thakur’s win and caste politics of selective purity in Hindutva; The feel-good narrative and what it conceals Extract 5 SEO-friendly keywords as tags. Output only keywords, comma separated.

Hashtags: #Maithili #Thakurs #win #caste #politics #selective #purity #Hindutva #feelgood #narrative #conceals