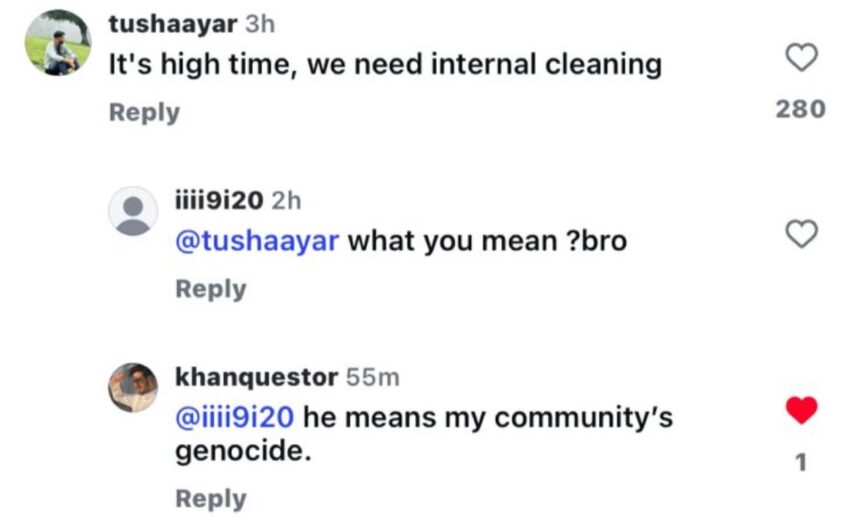

Hours after the car explosion near Delhi’s Red Fort, social media had already chosen its “culprits.” On a reel posted by Instagram influencer Prafful Garg, showing an unverified image of a man beside a similar car, one user wrote, “It’s high time, we need internal cleaning.” Another replied, “He means my community’s genocide.”

That exchange captured how quickly grief mutates into hate. Before investigators confirmed even the basics, Muslims were again declared guilty by default.

Within minutes, familiar phrases appeared across X, Instagram, and YouTube:

“Aur Namaz ka time 6:51 tha, taki unka koi na mare.”

“Dushman sirf border ke uss parr nahi hota, ghar ke bhitar bhi hota hai.”

“Padha likha Abdul jyada khatarnak hota hai.”

“Peaceful community again.”

“Matlab clear hai, chahe ye doctor bane ya engineer, karne inko blast hi hai.”

“Desh me jitne bhi Muslim study center hain, vo band kar dene chahiye.”

Each one repeats the same message that being Muslim is an inherent threat.

Manufactured suspicion as spectacle

While police urged restraint, several Hindu right-wing journalists turned speculation into primetime certainty. Senior journalist Rahul Shivshankar claimed “terror has a religion,” linking the explosion to unrelated arrests of Muslim doctors. India Today’s “open-source investigation” described the site as “opposite a temple,” naming only Hindu and Jain places of worship while ignoring the dozens of mosques nearby.

This selective framing has been perfected since 2020, when online hate helped inflame the Delhi pogrom that left at least 53 people dead, most of them Muslim. Human Rights Watch documented how days of social-media calls to target “traitors” and “infiltrators” preceded mobs attacking Muslim homes and shops.

The numbers behind the rage

The 2024 Center for the Study of Organized Hate (CSOH) reported that 37 percent of all hate-speech incidents in India targeted Muslims. Three out of four cases of dangerous speech, meaning posts likely to incite violence, began on social media, with Facebook hosting nearly 75 percent of them.

A 2024 study in PNAS Nexus by D’Souza et al. found spikes in pro-Hindu nationalist hashtags directly correlated with outbreaks of communal violence. The correlation vanished during internet shutdowns, showing that online hate fuels real-world aggression.

A separate 2024 Frontiers in Communication study found Islamophobia spreads fastest when disguised as concern. Messages like “they are plotting” or “they are multiplying” travel faster because fear feels like vigilance, not prejudice.

When algorithms reward anger

The same CSOH report showed that posts expressing anger or disgust gained almost twice the engagement of factual updates. Outrage is profitable.

Linguist Saima Hatem calls this “the step between exclusion and elimination.” When hate turns into casual banter, violence becomes predictable.

From screen to street

This is not a metaphor anymore. The Supreme Court’s comment the morning after the Red Fort blast, calling it “the best morning to send a message” while denying bail to a Muslim man under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, reflected how public sentiment echoes through institutions.

The same pattern was visible during the 2020 Delhi violence, when clips of incendiary speeches from political rallies circulated online hours before mobs mobilised. What began as digital vilification reappeared as physical assault.

The cost of living online as a Muslim

The 2024 Digital Minorities Survey by the Indian Institute of Peace and Conflict Studies found that 82 percent of Muslim respondents encountered Islamophobic content weekly, and 47 percent said it discouraged them from expressing opinions online. Researchers called this “anticipatory anxiety,” the expectation of bias before it appears.

That anxiety bleeds into everyday life. It shapes how landlords treat Muslim tenants, how employers scan surnames, and how police interpret intent. The Frontiers in Communication study noted that people repeatedly exposed to online hate reported higher anxiety and lower civic participation. Digital hostility becomes lived exclusion.

Hate that pays and hate that kills

Platforms rarely act until public outrage peaks. The CSOH audit identified 219 explicit posts inciting violence against Muslims that stayed online for weeks despite multiple reports. Delayed moderation is not a technical glitch. It is a business model.

Meanwhile, political speech and television coverage continue to push what can be said without consequence. The Centre for Media Studies found that identifying the religion of accused individuals before verification increased communal hate posts threefold within 24 hours.

From Delhi pogrom to now

The Delhi pogrom was not an exception. It was a rehearsal. The same vocabulary of hate that flooded social media in 2020 reappears today, more fluent, more coded, more confident. Each crisis becomes a stage for moral panic, and every viral comment normalises a level of cruelty that once would have shocked.

The rhetoric of “cleansing” does not emerge from nowhere. It grows in an ecosystem that rewards anger, protects misinformation, and punishes dissent.

What must change

Social-media companies must act faster and more transparently. Law enforcement must apply hate-speech laws consistently. News outlets must stop identifying religion before facts.

Beyond institutions, citizens must refuse to amplify hate. Reporting abusive posts, countering misinformation, and refusing to forward rumours are not minor acts. They are moral ones.

Words before violence

The online aftermath of the Delhi blast was an act of collective blame. When a comment calling for “cleansing” earns applause instead of condemnation, silence becomes complicity.

This pattern of digital to physical hate is unfolding even as these words are being written. India’s democracy depends not only on free speech but on the refusal to normalise hate. Genocide begins with unchecked words, not weapons.

To confront this continuum, from comment sections to courtrooms, India must decide what message it truly wants to send on its next “best morning.”

Aasma is a Delhi-based writer and communications specialist focusing on media, identity, and digital culture.

The post When a comment calls for cleansing appeared first on Maktoob media.